Part of what gave the “Roaring Twenties” its name was the way “horseless carriages,” as they were first called, made so much more noise than horses.

The decade’s accelerating pace and rising decibel count is really the story of the internal combustion engine and its revolutionary impact on road transport, in the air, and on water. The internal combustion engine-powered not only passenger vehicles and trucks but early buses, airplanes, and speedboats. On any given day, you could hear a roar just about anywhere.

Engines had been evolving since the late 1700s, and dozens of scientists, inventors, and engineers played roles developing them, with patents being granted as early as 1807. In 1859, Belgian-French engineer Étienne Lenoir developed the first commercially successful internal combustion engine. Twenty years later, German engineer Nikolaus Otto came up with its first modern version, using petroleum gas for fuel. Two decades after that, German mechanical engineer Rudolf Diesel invented a more fuel-efficient system and, in 1897, successfully tested his Diesel engine, which required heavier, more robust construction than a gasoline engine.

Long before that, way back in 1867, the year of Confederation, the first automobile in Canada had been built by Henry Seth Taylor at Stanstead, in Quebec’s Eastern Townships. It was run by a steam engine. In the early 1900s, these had been improved, and at least one early automobile in Muskoka was steam-powered. Electric motors were also in the running, and in time, Diesel engines, too, would be developed for passenger cars.

But for a variety of reasons, the noisy gasoline-fueled internal combustion engine became most popular, then dominant.

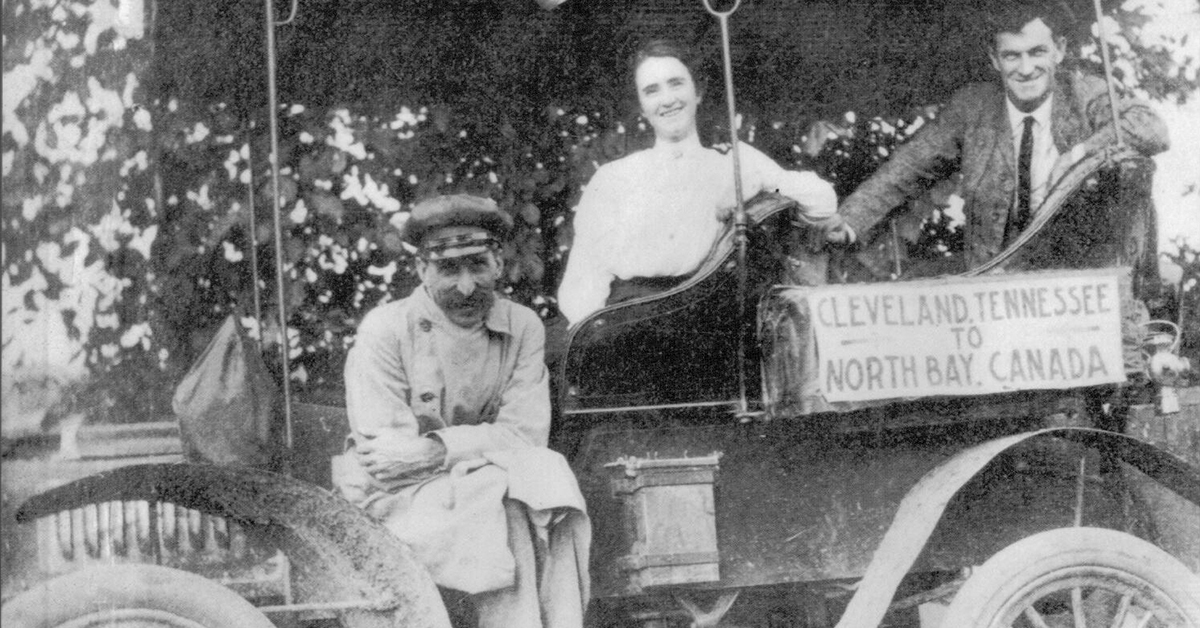

Up to the First World War, about 40 motor vehicles could be heard puttering around Muskoka. The first in Bracebridge was a 1910 Russell-Knight touring car, owned by lawyer Arthur Mahaffy who was also Muskoka’s member of the provincial legislature. In October 1910, Huntsville’s Dr. Jacob Hart, who’d built the town’s first hospital, was back in the news driving its first motor vehicle. Hart told the Forester for its front-page story he expected to take his McLaughlan-Buick “out into the countryside to attend patients.”

Another Muskoka doctor, Peter McGibbon of Bracebridge, also switched from horses to automobiles and, by 1914, was piloting a roomy, comfortable, and swift 35-horsepower Overland through town and countryside – at least to the extent Muskoka’s treacherous roads permitted. Muskoka’s first woman car driver was, it appears, enterprising Mabel Brown. She owned and operated her own main street millinery shop in Bracebridge before marrying Dr. McGibbon. She used the Overland when he was performing surgeries.

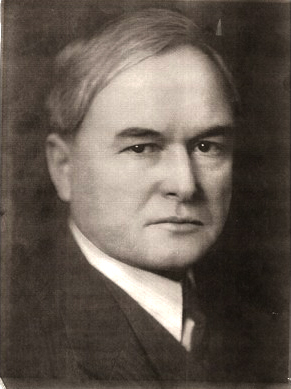

Dr. Peter McGibbon – Bracebridge.

Dr. Peter McGibbon – Bracebridge.

In Gravenhurst, too, doctors at the tuberculosis sanitariums and businessmen of the town were now among those driving a variety of cars.

Automobiles were also finding their way to Muskoka’s villages. From as early as 1907, Baysville’s first cars were driven by the hotel-owning Hendersons and touring guests staying at their resort who’d adventurously driven up the Bobcaygeon Road to Lake of Bays. By the end of the war, Port Carling’s first automobile would be owned by William Massey, tugboat engineer, livery stable owner, and skillful practical mechanic who loved engines so much he would soon open the village’s first garage as well to service cars. “Cars,” of course, was short for carriages, itself an abbreviation for “horseless carriages.”

Automobiles were expensive. Most came from small Canadian plants turning out just two or three a day. Many were custom-made, making them pricy. Regular folk considered them a plaything for the rich, something they’d never own.

That 1910 Russell-Knight car Muskoka’s MPP was driving shows more about the state of pre-war vehicles. For instance, it was called a “touring” car because it had both front and back seats. The driver could take enough passengers to qualify the trip as a tour. Nearly all touring cars held 5 passengers, but some had fold-down seats attached to the back of the front seat, enabling car salesmen to promote them as 7-passenger automobiles.

A car with a single seat was called a “roadster” – which sounds like more fun, a pioneer sports car. At the back of some roadster models, where we’d now find the trunk, a couple could ride in a separate area called the “rumble seat” – even more fun.

Mr. Mahaffey’s car had other notable features: the back seat was higher than the front one, enabling touring passengers to enjoy a better view and more wind in their faces. All cars in this era were open to the elements.

What about warnings? Horse-drawn vehicles could be heard by bells attached to their harnesses, but automobiles, like bicycles which had become a rage since the 1890s, were equipped with a warning horn, as they are today. It was installed in front of the dashboard and the driver honked by squeezing a large rubber bulb on the steering column to push air through the horn. By 1908 a variation called a “Klaxon” – a brass-tube horn with an even sharper warning blast – was fastened beside the driver, who operated it by jamming down on a plunger. Also a large brass bell was part of this arsenal, which the driver could ring with increasing urgency to warn of an impending crash.

What else? Mr. Mahaffy’s Russell-Knight, like most cars, had a four-cylinder engine, though some models had six. None could be started remotely with a fob like today, though you did have to be outside the vehicle to get it going. A driver hand-cranked the engine while standing at the front of the car.

Headlights operated on gas, side-lamps on coal-oil, which was used to illuminate the tail lights. They showed green to the left, red at the rear, with a clear light at the right shining onto the leather licence plate displaying the vehicle’s registration number. Before long it was upgraded from leather to more durable metal.

Nobody needed a driver’s licence. Everyone had the right to drive their own car, just as they did their horse, or boat.

At first, there were no garages to service autos. Gasoline was sold at pharmacies because licensed pharmacists were trustworthy for handling dangerous liquids. Then hardware merchants, who sold coal as fuel for engines and furnaces, considered themselves just as equal to the task of fueling cars. In Bracebridge by 1914 gasoline could be bought for 20c a gallon at Ecclestone & Bates Hardware Store on the Main Street. A clerk carried it out in a 5-gallon can and poured it into the car’s tank through a funnel with a chamois for a filter. Some motorists began keeping a barrel of gasoline in their garage. Car owners did their own grease jobs, filling and screwing down grease cups.

Tires were a real problem.

Completely smooth, no tread. Wheels spun even in mud puddles. When roads themselves became muddy, drivers put chains on the tires, standard equipment in the car, to give traction. Flat tires were common, which is why a couple spares were carried, perhaps even more when motoring up to Muskoka from Toronto – a trip requiring many hours, even more when changing flat tires. Drivers inflated them by hand pump.

The brakes on every automobile were just two-wheel and mechanical. No vehicle had windshield wipers, nor – especially bad when bouncing over Muskoka’s rough roads – shock absorbers.

For car trouble that a motorist could not solve on their own, most communities had somebody who could diagnose the problem and make a fix. In Bracebridge, best bet was Bill Simmons, superintendent of the town’s electric and water systems. He’d help, gratis, but if heavy work was needed, the car was towed by horses to the foundry where a fee was charged.

For ceremonial occasions especially, automobiles began replacing horse-drawn vehicles. In late July 1914, on the very cusp of world war, virtually every car then in Bracebridge marshalled at the train station, fully polished and fueled, waiting in a procession to transport Canada’s Minister of War Sam Hughes and two dozen District dignitaries. When the hero of the hour arrived aboard his special military train, two town bands played, hundreds cheered, and all fifteen automobiles, bearing Hughes and the entourage, rolled through town to a boisterous pro-war rally at Memorial Park. While people along the route waved at the officials, they gazed even more intently at the stunning array of passing Studebakers, Overlands, Chevrolets, Fords, and McLaughlan-Buicks being driven by their proud owners.

So there’s a snapshot of early automobiles in Muskoka. Let’s now turn to how technologies that rapidly advanced during the highly mechanized war became extended for civilian purposes in peacetime, and in turn, how the Roaring Twenties motor cars began altering the very character of Muskoka itself.

By the end of the war, through 1918 and 1919 changed men came home to a different Muskoka. At first, Muskokans along with the rest of the world put things on hold and struggled for months through the Spanish Flu pandemic which claimed millions of lives across the continent and around the world. After all that, a new era for automobiles became an economic, social, and cultural revolution.

As speed of travel increased, distances seemed shorter, going places more convenient. Ontario, and the entire continent, was on course to become a network of connecting roadways. Automobiles, which before the war were few and owned by the wealthy, now gave new freedom to hundreds of thousands, then millions, of individuals in all ranks of society.

When carmaker Ransom Olds conceived of interchangeable components, assembly-line production became possible, reducing a car’s price to customers. Manufacturers began mass producing them, and people who previously owned a horse to pull their buggy or sleigh now bought a car. Birth of this dynamic new economy for automobiles brought far-reaching social changes, enhanced personal mobility, and created a new car-centric culture. In the Roaring Twenties, cars were all the rage.

Let’s look more deeply at how that happened and what it meant.

In the 1920s, Canada became the world’s most motorized country after the United States. Each year of the decade, an increasing number of cars, trucks, buses, and motorcycles were registered. The number rose from 408,000 new cars in 1920 to 1,235,000 by 1930 – that’s more than one and a-quarter million new vehicles in Canada every year. The auto industry went from eighth to fourth place among Canadian manufacturing industries. During the decade the amount of money invested in car-making more than doubled, from $40 million to $98 million.

Two factors, above all others, were behind these impressive numbers. One was Canada’s stiff 35{7b5a5d0e414f5ae9befbbfe0565391237b22ed5a572478ce6579290fab1e7f91} import duty on cars. This tariff wall caused American automakers to open branch plants north of the border. Although smaller car companies merely assembled new vehicles in Canada using lower-tariff American-made parts that they’d shipped over, the “big three” auto makers – Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler – opened factories that did more than assembly work. They actually built their vehicles entirely in Canada.

By manufacturing on this side of the border, the technically advanced and lower-priced vehicles were more easily distributed across the country and sold to Canadians. In addition to making competitively priced cars for Canada’s market, these American-owned subsidiaries, as Canadian companies, got a second benefit when exporting cars to any part of the vast British Empire. Thanks to “Imperial Trade Preferences,” this British system of lower tariffs created the Empire’s own common market. With Canadian-built motor vehicles, the Americans had, like a Trojan Horse, gotten themselves inside the fortified British enclave, enabling these U.S. auto makers to indirectly slip their products sideways without the high tariffs into British countries around the world.

As a result, Canada’s auto-makers soon became unique among Canadian industries, with fully a third of their manufactured products selling outside the domestic market.

In our last program, I talked about Canada moving into closer orbit with the United States after the First World War. A specific case study of what that looked like is what was happening in the automotive industry. It first began back in 1904, when Canadian auto making leaped ahead because Gordon M. MacGregor and several other entrepreneurs in the city of Windsor incorporated the Ford Motor Company of Canada, right after Henry Ford, American inventor and promoter, set up his production company in 1903 in Detroit, just across the river from Windsor. Using the Walkerville Wagon Company’s works, cars were assembled in Canada with parts ferried across the Detroit River – the beginning of Canada-U.S. automotive collaboration.

Then Canada’s most prominent pioneer in automobile manufacturing, Col. R.S. McLaughlan, switched production at his family’s prospering Oshawa plant. Instead of building sleighs and carriages, it now housed production of his McLaughlan automobile. This exceptionally fine vehicle’s only problem was its roaring loud internal-combustion engine. By 1908, McLaughlan inked a deal, orchestrated by financier William C. Durant who’d formed General Motors in the U.S., that solved his noise problem. David Buick’s quiet humming engines would be combined with McLaughlan-designed bodies.

The marvelous McLaughlan-Buick combo soon gained wide renown, including in Muskoka as the very first automobile in Huntsville.

Next, GM’s Durant offered Col. McLaughlan Canadian rights to the Chevrolet “Classic Six,” a 5-passenger touring car designed by racing-car driver Louis Chevrolet.

By 1918, with the United States finally in the war on the Allied side and demand for motorized vehicles of many types was rising steeply, McLaughlan Motor Company and Chevrolet Motor Company of Canada merged, with Col. McLaughlan the consolidated company’s president. Production on both sides of the border ramped up. Although steam and electric vehicles had a number of operating benefits, the edge kept going to the increasingly popular internal-combustion engine. South of the border, Detroit predominated, by building on the city’s well-established manufacturing base for horse-drawn carriages, bicycles, and boat engines.

North of the border, early years of Canadian car making saw thousands of automobiles roll out – including the LeRoy, the popular Russell, the Tudhope, the Thomas, the Galt, and others. But the small independent Canadian companies making those vehicles did not survive, a huge problem being Canada’s surplus of land and deficit of people. A single, consolidated, government backed auto-maker might have prevailed, as they have in other countries, but this was not the path Canadian and American capitalists chose. Instead, under private enterprise and burgeoning demands for motor vehicles, from 1918 to 1923 Canada became the world’s second-largest vehicle producer and major exporter – all related to the large-scale, big-business, private-sector, cross-border operations of North America’s auto-makers.

The advantage for Windsor, Oshawa, and other southern Ontario cities was proximity to Detroit as the automotive economies on each side of the Detroit River became increasingly entwined. With most cars sold in Canada being American models built by Canadian autoworkers, thousands of jobs, mostly in Ontario, were created in the motor vehicle plants. By 1929, this number stood at 13,000 full-time employees. Thousands more had jobs making the primary materials needed in building motor vehicles, such as tires and spare parts, while another legion of workers was deployed repairing and servicing autos. Beyond those producing and maintaining the many thousands of cars and trucks were millions more whose social and economic life was increasingly linked to motor vehicles and roadways.

Muskokans kept pace with all this. Gas could be purchased at roadside pumps. Service centres became profitable businesses by including along with gas sales such services as lubrication and other engine work, pressurized air for filling tires, water for radiator tanks, and basic body work. Local dealerships sold the different makes. One Huntsville car dealer, carrying Fords, advertised: “There are cars you cannot afford, and then there’s a Ford.”

As cars multiplied, roads needed upgrading. Town and village councils carried out street improvements, initially with residents along streets who wanted it petitioning for paving and then getting a “roadway improvement” charge on their tax bill for the improvement that raised their property values. The townships with longer connecting roads had fewer people and less money, so their concession lines and cross-country routes remained poor to terrible. The province generally left these matters to local government. As a result it was townships, with ratepayers voting their approval of spending on road construction stage-by-stage in plebiscites, that built the road between Bracebridge and Port Carling, today’s Highway 118 West.

In the 1920s response to the need for broader, bolder action on roads saw automobile clubs formed, a Better Roads Movement take shape, then a road-builders association emerge – and all three entities, along with municipal governments, ramping up pressure on the Ontario government to get with the new era – a pattern common across Canada, the U.S., and in Europe. The automobile clubs formed the Canadian Automobile Association, or CAA; south of the border, the same forces created the American Automobile Association, or AAA – and, echoing the Canada-U.S. pattern of making cars, these two organizations for those driving them also developed interlocking mutual arrangements.

In Muskoka, the Automobile Club helped locals and vacationers alike by plastering highly visible yellow-and-black directional signs along roadways and at intersections: Port Carling, 17 miles – Bala, 12 miles, Dorset, 26 miles. Particular roadway corners at the outskirts of Muskoka’s major towns and at highway crossroads became post-card worthy roadside symbols of the automobile era – dozens of these directional signs on a cluster of posts and utility poles.

The Bracebridge Automotive Club encouraged summer visitors by creating its well-equipped Kelvin Grove Motor Park for the touring public, charmingly located on the large bay below the town’s waterfalls.

Getting better roads became a mission of survival for a District whose vacation economy was a pillar of life. Because travel and transport in Muskoka’s early years centred on waterways – including when iced over in winter – the District’s difficult roadways with horse-drawn traffic remained secondary. So remaining a viable vacationland player in this new continental universe of touring automobiles, Muskoka now faced an existential challenge. In another broadcast, we can look at how that fate was confronted – as Muskoka’s traditional Steam Era tourism patterns began passing into history and the Age of the Horse became further eclipsed in the wake of the Roaring Twenties Automobile Revolution.

More Stories

Tips for Negotiating the Best Deal When Selling Your Car

5 Women That Shaped the Automobile and the World Around It (and Us)

Automobile retail sales see double-digit growth in February on robust demand