Let’s roll back the scrolls of time and picture ourselves in an alternate universe where cars are designed, engineered, built, and driven solely by male representatives of the Homo Sapiens species. Apart from loud pipes, humongous displacement, outrageous turbos, immorally oversized wheels, and heavens-shattering track battles, can you think of other one-minded approaches to motoring?

Ford Motor Company did, and it proposes a hypothetical vehicle that bears no mark of women’s contribution to automobile history. The short (and immensely hilarious) video below is a glorious praise to all the unsung heroes of the motor car universe. The following is a story about five women who made motoring better – some even without realizing their enormous beneficial contributions to gearheads’ safety and comfort.

Florence and Lotta Lawrence – brake and turning indicators, windshield wipers

Can you imagine today’s cars without brake lights, windshield wipers, GPS, or turn signals? Neither can I – although for a particular group of steering-wheel operators (I can’t call them “drivers”), the said lever appears to arm a nuclear bomb. That’s how cautious they are not to use the indicators.

The turn signal is a master safety improvement for driving that became the norm thanks to a movie star’s determination. She is Florence Lawrence, an American-Canadian actress from the silent film age – one of the first actors to have their name written on the silver screen.

She was a very well-paid actress in the early 1900s, and fame and wealth joined hands over her career. Having purchased an automobile in 1913, she quickly discovered a major flaw in its design. There was no practical way of forewarning fellow motorists about changing direction.

A practical thinker and hands-on character, she devised a way-pointing mechanism. A lever on the rear fender would rise or lower (by pushing a button on the dash) to indicate left or right. Another feature was the “full stop” sign on the rear – which was raised or lowered by pressing the footbrake.

In 1917, Florence’s Lawrence mother – Lotta Lawrence (her real name was Charlotte Bridgwood), came up with the idea of a windshield-wiping gadget. Unfortunately, neither she nor her daughter patented their inventions.

Ironically, one year after Florence passed away in 1938, Buick began installing turning lights as standard equipment on their 1939 models.

Dorothy Levitt – mirrors aren’t just for self-gazing

Another inspirational lady from the early days of the automobile was an Englishwoman from London. Her story is linked to horsepower and speed, and she has, at one point, set land- and water speed records. She started working as a typist for a car company manager. Still, the piston fever grew on her immensely and incurably.

An avid motorist, she participated in numerous races in Europe – both in the British Isles and on the continent – and was notorious for speeding. Not just during competitions, but also on public roads. In November 1903, she was fined £5 for fast driving in Hyde Park. One hundred twenty years later, that’s £777.82 in King Charles the Third’s money, the equivalent of $920.

She attracted a lot of media attention – a woman behind the steering wheel was scandalous, to say the least – and male hatred. Nonetheless, she raced a motorboat at 19.3 mph (31 kph) in 1903 – the first water speed record for motorized crafts.

In 1906, Dorothy Levitt set a new land speed record for women (gender equality was regarded as a criminal offense). Her diary laconically mentions, “Broke my own record and created new world’s record for women at Blackpool. Ninety horse-power six-cylinder Napier. Racing car. Drove at rate of 91 miles an hour. Had near escape as front part of bonnet worked loose and, had I not pulled up in time, might have blown back and beheaded me. Was presented with a cup by the Blackpool Automobile Club and also a cup by S. F. Edge, Limited. – Dorothy Levitt. October 1906”

In 1909, the 27-year-old stereotype-braking typist-turned-motoriste (with a feminine “e” at the end) wrote “The woman and the car. A chatty little handbook for all women who motor or who want to motor,” in which she advised women of proper road manners. This is an excerpt: “(…) the majority of work on a car (filling tanks, &c. &c.) can be done just as well if a pair of wash-leather gloves protect one’s hands. You will find room for these gloves in the little drawer under the seat of the car.

This little drawer is the secret of the dainty motoriste. What you put in it depends upon your tastes, but the following articles are what I advise you to have in its recesses. A pair of clean gloves, an extra handkerchief, clean veil, powder-puff (unless you despise them), hair-pins and ordinary pins, a hand mirror – and some chocolates are very soothing, sometimes!

…

The mirror should be fairly large to be really useful, and it is better to have one with a handle to it. Just before starting, take the glass out of the little drawer and put it into the little flap pocket of the car. You will find it useful to have it handy – not for strictly personal use, but to occasionally hold up to see what is behind you. Sometimes you will wonder if you heard a car behind you – and while the necessity or inclination to look round is rare, you can, with the mirror, see in a flash what is in the rear without losing your forward way, and without releasing your right-hand grip of the steering-wheel.”

I wish my driving instructor had been this considerate and thoughtful when I was in driving school. Nonetheless, Ms. Levitt gave more practical advice on means of self-defense for lone-driving women. I will not say what it was, but it is a UK-patented invention of an American named Samuel Colt.

Dorothee Pullinger – The first car designed and built by, with, and for women

Daughter of a French engineer, this extraordinary woman began her professional career in an automobile factory. Her father was a manager at Arrol-Johnston, and his daughter got a job as a drawer – draughtswoman was the British terminology in 1910.

In 1914, Dorothee applied to join the Institution of Automobile Engineers. She was refused because “the word person means a man and not a woman.” The hardy lady didn’t bat an eyelid and continued her work at the car plant.

The Great War broke out, and Dorothee was appointed manager of a munitions facility operated by Vickers. With most men sent to the frontlines, women were the workforce in most armament factories (apparently, making high-explosive shells wasn’t a “person-only” occupation). By 1918, Ms. Pullinger had seven thousand female workers under her management as Lady Superintended.

With a Membership of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (awarded in 1920 for her wartime work), the entrepreneurial Dorothee switched her attention to carmaking. A branch of Arrol-Johnston became Galloway Motors Ltd. It began producing an automobile designed for smaller-framed female drivers, with Dorothee Pullinger, MBE, as manager and director.

The Galloway automobile had a four-cylinder 10-hp side-valve 1.5-liter engine and rear-wheel drive. It had leaf springs suspensions and three- or four-speed gearboxes. The most striking particularity of the automobile was its gender-oriented design.

The lady-car was much lighter and smaller than most other man-driver-purposed cars from the early 20s. The car was described by Light Car and Cycle in 1921 as “a car built by ladies, for those of their own sex.”

Gear and brake levers were placed inside the car rather than outside by the driver’s door. It has a more reliable engine than the era standards, a raised seat, extra storage space, and a smaller steering wheel. Also, the dashboard was lowered, and a rearview mirror was added (Dorothee must have read Dorothy’s book).

The Galloway was the first mass-produced gender-centric automobile. Only 4,000 units were assembled between 1920 and 1925, and fifteen are believed to still exist today. However, while it did not set a milestone in carmaking, the company was a game changer for the labor environment.

It adopted the colors of the Suffragettes and had two tennis courts on its roof for employees. Critically, it hosted an engineering college for women. Here’s the best part of the Pullinger story – apprenticeships lasted three years for women, but five for men because it was believed women were faster learners.

Hedy Lamarr – the Hollywood star with a knack for anti-Nazi technology

Chances are you’re reading this story on a mobile device – a phone, tablet, laptop, or even the car’s display. Thank an Austrian actress for this wonderful facility – the Wi-Fi – that dramatically shapes our lives today.

Hedy Lamarr was a successful actress in Europe in the ’30s, and her fame tied her destiny to a wealthy Austrian industrialist. Unfortunately for the charming movie star, her husband’s links with German and Italian high-ranking state officials did not go well with her Jewish origins.

In 1937, she fled to England and America and continued her acting career in Hollywood. However, on-camera performance was her talent, but her actual call was engineering mastermind. In 1940, Hedwiga Eva Kiesler (Hedy’s official name) met the like-minded movie score composer George Antheil.

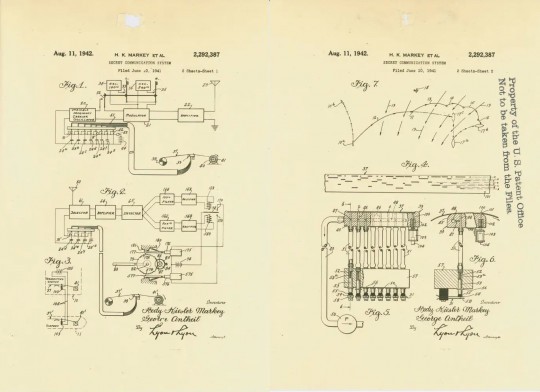

Later on, after America entered the war, Hedy and George – hearing the news about the submarine warfare – conceived a radio guidance system for US Navy’s torpedoes. The invention involved “frequency hopping” radio waves, with both transmitter and receiver simultaneously switching to the same broadcast frequency. This prevented the interception and jamming of the signals, allowing the torpedo to hit its target.

US Patent Office number 2,292,387 granted the duo their copyright on the clever invention. Still, the Navy didn’t buy it, and Lamarr and Antheil made zero profit from their concept. The idea was genius, but the military masterminds misunderstood one little detail, and the whole affair sunk.

A torpedo would be equipped with a radio receiver. The ship launching the torpedo would have a transmitter tuned to the same frequency. A player piano-similar mechanism would sync the end devices on a predetermined pattern.

Allegedly, the prospect was rejected because someone in the Navy committee mistakenly understood the torpedoes had to fit an actual player piano. Nonetheless, the system saw real-life application two decades after its invention, during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

Modern broad-spectrum communication systems (like Bluetooth or Wi-Fi) are derivative of this Hollywood-devised invention. The tech-savvy artists received posthumous recognition for their creations. Hedy Lamarr is known outside showbusiness circles as “the mother of Wi-Fi.”

Dr. Gladys West – how men learned to get directions

The map light no longer fits the bill among today’s cars’ countless conveniences, which is perfectly reasonable. With Global Positioning System Navigation, who uses printed maps? I’ll tell you about one person who still does – the inventor of GPS.

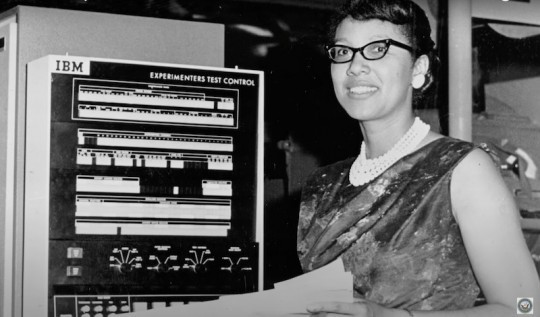

Gladys West has the honor of closing our list of five women who changed the automotive universe. She is 92 years old, and 42 of those years were spent working at the Naval Proving Ground in Dahlgren, Virginia. She retired from the military base in 1998.

A brilliant mathematician, she devised a highly complex – and astronomically complicated – mathematical model of the Earth’s satellite geodesy. In average Joe English, this is “the measurement of the form and dimensions of Earth, the location of objects on its surface and the figure of the Earth’s gravity field by means of artificial satellite techniques.”

Did I mention Dr. West did this in the early ’60s, soon after the first artificial satellites began orbiting Earth? Initially, she didn’t have the luxury of using computers for her work. It was all pen and paper – and her great mind. Later, she wrote a computer program to compile increasingly accurate models of the Earth’s shape.

That was during the ’70s and ’80s, when computers – primitive, by today’s standards – became powerful enough to help science advance faster. Her accomplishments list could fill the shelves of a public library, and she was inducted into the United States Air Force Hall of Fame in 2018.

Dr. Gladys West rose high above her time threefold. First, she made her way up – a very long and arduous journey – in a men’s world. Secondly, she gifted humanity with something we all take for granted because it is just one screen tap away.

And third, she emerged victorious – at great cost – by overcoming an obstacle of incommensurable magnitude: the racial segregation prejudice. In the rural South of the mid-’50s, an African American woman had much to fear for her safety, let alone aspire to reach for the stars.

Today, when we need to drive from point A to point B, but don’t know what route to follow, we revert to one of the countless navigation apps. In seconds, we receive an incredibly high amount of information about the journey, from traffic to weather to accommodations and leisure pastimes.

Well, Dr. Gladys West – an accomplished scientist, genius scholar, and brave woman – prefers the simplicity of folding motoring maps. In a November 2020 interview, she stated, “I’m a doer, hands-on kind of person. If I can see the road and see where it turns and see where it went, I am more sure.”

From rearview mirrors to Wi-Fi to turning lights and windshield wipers – if those amazing women had strayed away from their true selves, perhaps today’s cars would have been entirely different. From the bottom of our engine blocks and cylinder heads: Thank you, Ladies!

More Stories

Tips for Negotiating the Best Deal When Selling Your Car

Automobile retail sales see double-digit growth in February on robust demand

Automobile: Automobile retail sales see double-digit growth in Feb on robust demand