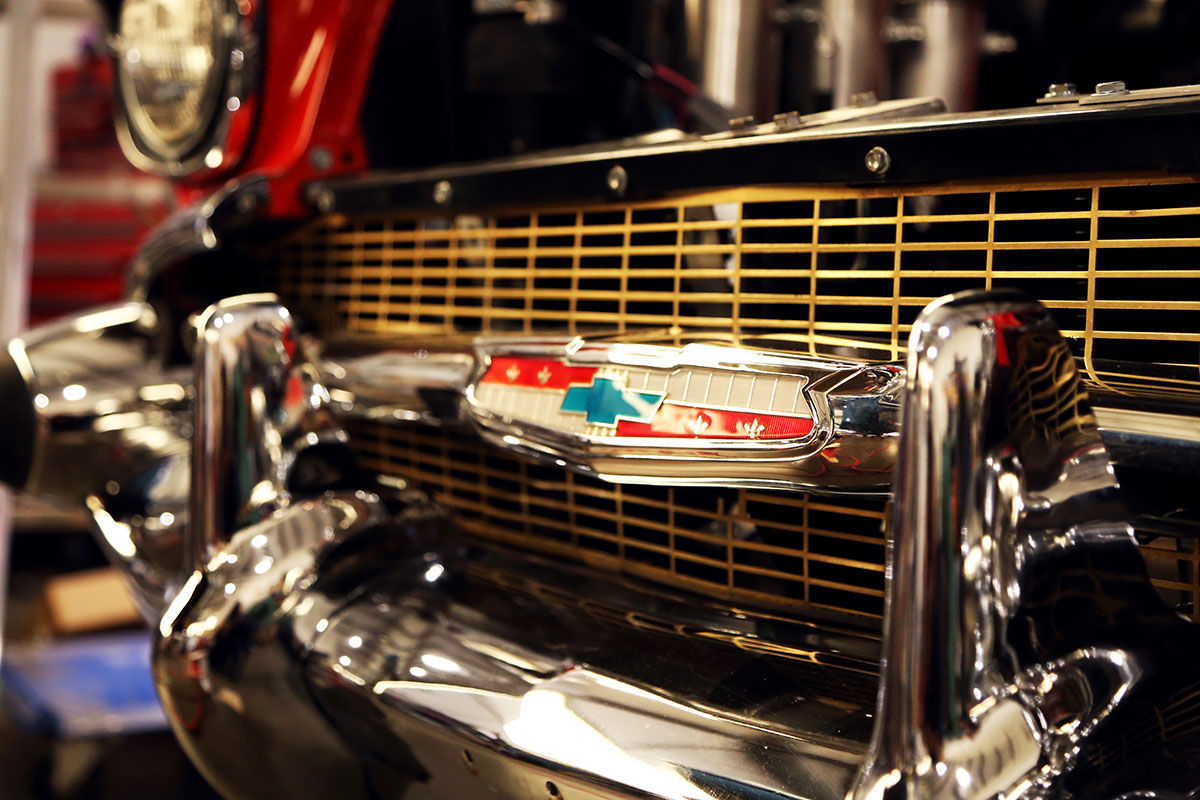

The red 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air sits a foot off the ground, glinting ruby-like in a small workshop in Parksville, B.C., its hood and engine gone. The car is getting serious attention from mechanics, but something is curiously missing from this otherwise conventional garage.

The smell of gas.

The men clustered around the Bel Air haven’t stripped it down for routine servicing. They intend to replace the gas-gulping engine in this 65-year-old automobile with an electric motor.

You might think gearheads who love classic cars would celebrate that as a perfect expression of recycling in this era of climate change. But many consider the transplant being carried out by Canadian Electric Vehicles, or canEV, to be sacrilegious.

Immune to such controversy is Todd Maliteare, owner of canEV since 2016. At age 47, Maliteare has a background in transport vehicles, and his current job is developing a line of electric utility trucks that can be used in places like airports and university campuses.

But then Chris Webb came calling.

Webb, 63, owns Webb Motorworks, a Victoria, B.C., company that designs custom aluminum casts for electric motors in the design of classic engine styles: in particular, the “small block Chevy” and the Ford flathead V8 and V12.

His products had taken him to the Specialty Equipment Market Association show in Las Vegas, a mecca for people in the business of car modifications. And there he realized the engine casts he makes could be part of a larger package. Adding in batteries, transmission and mounts on the engine cast would allow someone to bolt the entire collection into a car, turning it electric with minimum effort. Webb calls the kit the Cyberbeast.

The result is an electric motor that, despite its lack of pistons, looks like the combustion engine it replaces.

Webb’s work, which he posted on Instagram, piqued the interest of the owner of the Bel Air, who wanted to give it an electric Cyberbeast heart and show off the result at the next SEMA. One car turned into three, and Webb — who had an inkling that he might be onto an untapped market — agreed.

The only trouble? Webb didn’t have the expertise to make these cars electric. He needed the help of a friend.

“So, I called Todd,” Webb says “I said, ‘Hey Todd, this guy wants three cars. I can’t do this by myself. You interested?’ And Todd’s like, ‘No. I’m busy doing trucks.’ And I said, ‘Well this is a really cool project, c’mon Todd!’

“And then Todd agreed. Unfortunately for him.”

Because when Webb made that call to Maliteare in mid-2021, the SEMA show was only five months away. Not only that, but the world had just dragged itself out of pandemic lockdowns and straight into a supply-chain crisis.

Three cars. Five months.

The clock was ticking.

Photos by Pallavi Rao.

Held in the first week of every November, the SEMA show is the calendar event for car nerds and pulls in close to 100,000 attendees. All the major car manufacturers turn up, showing off their latest models and concept cars. Ford, Toyota, Jeep and General Motors tussle for space with smaller parts manufacturers.

Maliteare and Webb knew that if their cars were to impress SEMA, they couldn’t just be props and they couldn’t be half-done. Their audience would know if their prototype wasn’t rigged up to work correctly and if it didn’t run.

But the conversions meant entering uncharted technical territory, and canEV‘s crew is five mechanics.

The first big challenge was the parts. Many are specific to electric cars and must be shipped from around the world. The batteries had to travel all the way from China, bang in the middle of a growing supply-chain crisis.

“It was brutal,” Webb says. “We had to pay $17,000 just to get them air-freighted here.” They still took three months to arrive.

Now the crew had to assemble a mechanical jigsaw puzzle. Many of the systems that canEV is dealing with are not made at scale, don’t come with full instruction manuals and often are not made for what canEV has in mind for them. The team builds out schematics, figures out what parts they need, puts them together, and hopes that they work. If they don’t, it’s back — literally — to the drawing board.

“Todd’s pulled all his hair out,” Webb says at one point during the project. “His boys are ready to quit and his wife’s ready to divorce him because they’re all working 14 hours a day.”

Three cars. Five mechanics.

And now two months.

Photos by Pallavi Rao.

The cars in this story belong to Brian Dilley, a digital entrepreneur who helped create the Android version of an app that was bought by a Chinese company to fold into one that they were building — which turned out to be TikTok.

Dilley stayed on until TikTok launched in the U.S., then left to build distribution for another startup, Blockfolio, just as cryptocurrency began taking off. Another acquisition later and Dilley is the founder of yet another startup called Quickride.

All of this has left Dilley, who lives in Los Angeles, with what he calls “some money to invest.” His past experience working at an auto parts shop gave him an appreciation of classic cars and a vague intention to one day fix up his own “beater” as a hobby project. But he also knew that a ’57 Chevrolet Bel Air was a car on his dad’s bucket list to own. And Dilley decided now was the time to make that dream come true.

His daughter offered a suggestion. “You know what would be really cool? If it was electric.”

Across the border in Canada, a similar father-daughter conversation was happening. Emily Webb, Chris Webb’s eldest daughter, always loved how riding around in her dad’s restored 1956 MGA Roadster drew attention.

“People on the street wave at you,” she says. “And when you’re eight-years-old, that’s pretty fun.”

Despite growing up in and around the garage, helping her dad with his latest projects, and now acting as the CEO of Webb Motorworks, Emily never felt like she had the mechanical skills to own a hot rod.

“If I broke down on the side of the highway, I couldn’t troubleshoot the engine,” Emily points out.

Then she came across a California-based outfit that did electric conversions. Emily sent the link to her dad.

“At first he was like, ‘Electric vehicles are stupid. I’m not interested at all,’” Emily says, chuckling.

She found reasons to convince him: how powerful an electric car can be, how easy to maintain. Eventually the kicker came: “This is, potentially, the only way I can have a hot rod of my own,” Emily told her father, “if it was electric.”

Chris Webb was sold. And from that discussion grew the Cyberbeast.

Back in California, Brian Dilley was digesting his own daughter’s vision of an electric classic convertible.

“I was like, ‘Man, that would be so cool’,” Dilley says. When he discovered Webb Motorworks, he reached out about the Cyberbeast with its old-school look. By the time Webb and Dilley were done talking they arrived at an agreement. They’d do three electric conversions to show at SEMA, and Dilley would foot the bill.

The ’57 Chevrolet Bel Air convertible was promptly packed off to Vancouver Island. Webb then scouted a ’69 Chevrolet Camaro Z/28 and a ’32 Ford Deuce Coupe to round out the offerings. Todd Maliteare and canEV came on board.

All systems go.

Photos by Pallavi Rao.

Emily Webb and Camrynn Dilley are two faces of the worldwide electric car movement accelerated by the worsening climate crisis. Tailpipe exhaust from combustion engines on the roads create 12 per cent of annual greenhouse gas emissions. That’s more than the emissions released from the production of iron, steel, oil and gas combined. Going electric, obviously, eliminates those tailpipe emissions.

At the same time, electric cars are no perfect answer. They use twice the copper and manganese required in a conventional car, according to the International Energy Agency. They also require significant amounts of lithium, nickel, cobalt and graphite, mostly for their batteries, that are not used in gas-powered cars. Mining for these extra materials generates its own emission problems.

Then there is where the electricity needed to fuel these cars originates. For countries like China and India, where electricity is still generated by burning coal, electric cars would put far less of a dent in emissions. It’s only if a person’s primary-use vehicle draws electrical power from low-carbon fuel systems (such as wind, solar, hydro or nuclear) that emissions can be reduced significantly — up to nearly five times, research shows.

That’s a lot of ifs. Nevertheless, electric vehicle sales have hit new records every year since 2012, with more than 10 million on the road in 2020 compared to less than 10,000 a decade ago. Most automobile giants now offer electric versions. More than 38 countries offer an incentive to help people to buy an electric car and, within Canada, B.C.’s are among the more generous.

Going electric is no longer just a badge of status for environmentalists and techno-geeks. “Elon Musk made it cool,” Webb says.

The classic car market is worth $30 billion and projected to grow at nine per cent each year till 2030. And canEV is far from the only company doing electric conversions for vintage specimens. Soccer legend David Beckham is an investor in a British company that electrifies highly expensive luxury classics, including those made by Rolls-Royce and Jaguar.

But canEV’s ultimate goal is to make their kits popular and idiot-proof so car owners can do the electric conversions as a weekend project. Webb has the same idea with the Cyberbeast.

First they both needed to get it right for SEMA.

Photo by Pallavi Rao.

It’s midway through October 2021, two weeks before Vegas. One week before the cars ship out.

Tensions hang heavy in canEV’s workshop. Maliteare is visibly distracted and worn out. Around him his mechanics are clustered in two groups. One group is working on the ’69 Camaro, laying the cabling that will connect the batteries in the hood to the ones in the back. Its engine, a bright cherry red, gleams in the gloom.

An electric conversion kit, meanwhile, has been sent off to Dilley in Los Angeles, where he will hook it up in the ’32 Ford with a mechanical wiz friend named Bryan Garcia. The other group at canEV’s workshop is putting together the Bel Air’s engine.

No doubt the ’57 Bel Air is one of America’s most revered classic cars. The two-door convertible model that canEV is converting had a manual three-speed gearbox and 140 horsepower under the hood. At the time of its manufacture, it was the height of glamour and technology: some models included power windows and steering, as well as a radio, and all of them had chrome hooded headlights and a distinctive long tail fin design. A brand new ’57 Bel Air cost US$2,511 in 1957 (equivalent to about $27,000 today) and approximately 700,000 models were produced and sold that year.

Today, the same car goes for anywhere between $50,000 to $130,000. Dilley paid $60,000 for his dad’s gift.

A group of men huddle around the small crane holding up the Bel Air’s electric motor. Scott Rauscher, in charge of electronics, Adam Wicikowski, a parts designer and Sam D. Monge-Monge, who put together the cooling for the batteries, are all trying to lower the motor into Webb’s V12 small block Chevy cast.

When the cars arrived at the shop, the first thing canEV did was take out the original powertrains of the cars and put them aside. Then they scanned the interiors to figure out their dimensions. They made a list of materials and equipment they’d need, what they could order in a reasonable timeframe, and what they’d have to develop in-house.

The company also wants the engines to look and sound like the gas-powered originals. So Wicikowski designed, and then 3D printed, a fake carburetor for both cars. Sound comes from speakers connected to the accelerator.

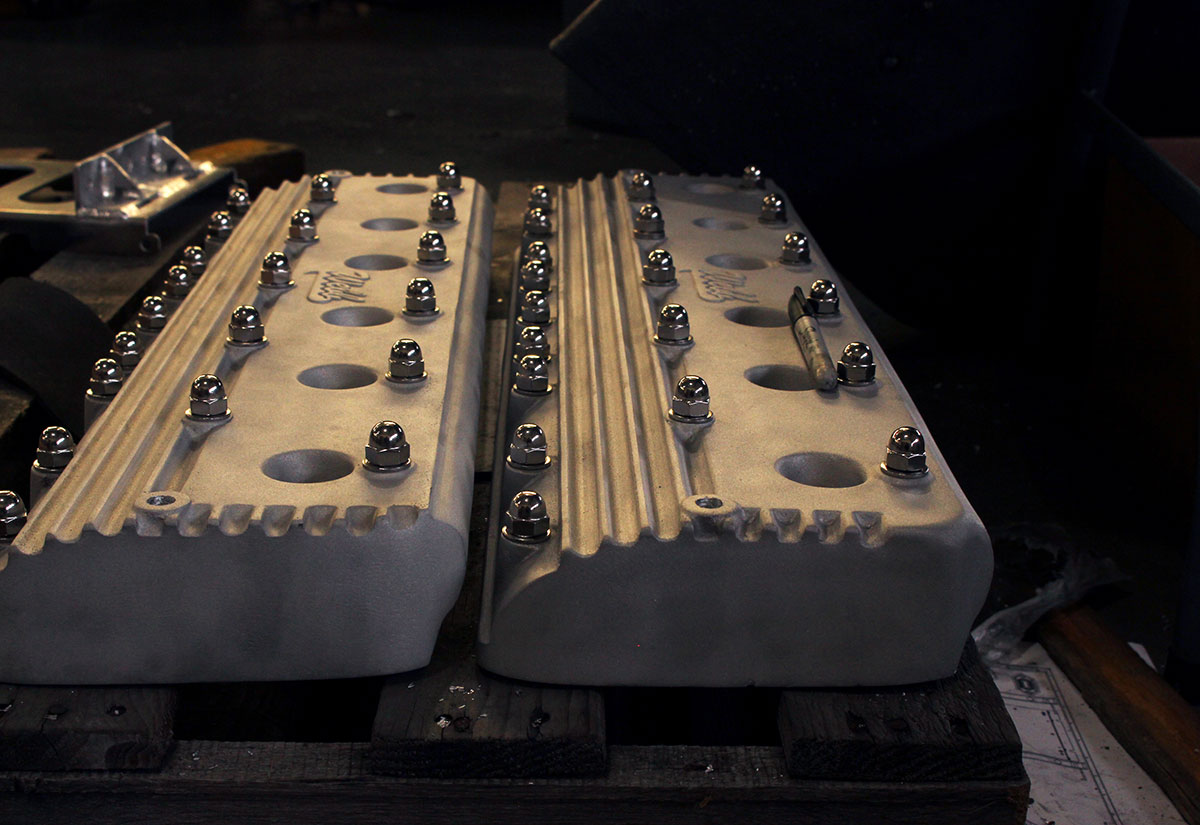

The casts Webb delivered to canEV were too small to fit all the electric components and had to be cut, resized and then rewelded. A wiring diagram was developed from the ground up. It sits beside the group putting the Bel Air’s engine together.

Into the aluminum cast goes two battery packs, the electric motor, an inverter to convert DC to AC, a charger, two computers (one for the battery, one for the engine), liquid cooling pumps and a host of cables to connect everything. It’s like shoving your entire closet into one travel suitcase with one condition — nothing can be squashed together.

The mechanics are bent over, lifting, prodding, poking and swearing freely. There’s so little space inside the cast that you can’t see inside properly. Rauscher eventually pulls out a tiny periscope camera that attaches to his phone on the other end. He drops the camera into the mess of electronics inside and peers at his phone screen to check crevices.

The V12 small-block Chevy cast is giving the Bel Air crew some trouble. They can’t get their hands in far enough to check if the cables have anything pressing down on them. The mechanics’ faces are tight with strain. Rauscher, architect of the wiring diagram, is particularly worried. He has one eye on the camera feed and one eye on everyone else.

Wicikowski’s hand strays too far. “Watch out!” Rauscher calls out. “You’re near a live terminal!”

Wicikowski pulls his hand out gingerly and the group reconvenes for a discussion. Something is not right. They will have to yank it all out to figure out what.

“To do three cars over five months is asking for a lot,” says Maliteare. “It should have been one car, over one year.”

Photos by Pallavi Rao.

One hundred and fifty days after it first arrived on Canadian shores, the ’57 Chevrolet Bel Air is brought back to life. Instead of a sharp cough from the exhaust and then the churn of its gas engine, an electric whine filters into the autumn air. That whine is accompanied by whoops and cheers from the canEV team.

The cars work.

Now to get them to SEMA. They are loaded on trucks which are ferried from Parksville to Vancouver and then driven across the border to Washington state, where there’s a snag. The driver who had been enlisted to haul the trucks to Vegas is sick and no replacement is readily available.

“We just couldn’t catch a break,” Webb recalls. “The cars were just sitting there, with nowhere to go.”

Then Dilley comes to the rescue, finding a licensed driver and paying him a premium for the last-minute job.

So the cars do make it to Las Vegas where the gathered team — including Emily Webb — awaits the verdicts of the public and prize judges. Over four days, Brian Dilley’s passion project attracts thousands of visitors, widespread media interest and three awards. The team is ecstatic, and unmistakably proud.

“In my opinion,” Webb says at the time, “Brian owns the three coolest hot rods in the world.”

But cool is a matter of opinion. For purists who believe that a vintage car is a conserved artifact, these transformations are heresy. The Fédération International des Véhicules Anciens, which is a worldwide federation of historic car clubs, categorically stated in 2019 that they don’t support these conversions, because they don’t meet the federation’s values of “preservation, protection and promotion of historic vehicles.”

Webb’s Instagram posts drew attention from aficionados aghast at what he was doing. Some were crudely ridiculous; one poster asked if Webb had “grown a vagina” after the conversion.

Dilley took heat, too. In L.A., where he lives, he’d driven the ’32 Deuce Coupe Ford — made with Ford steel that’s 90 years old — to a meet-up outside a burger joint. There, an old man came up to him, admiring the car and pointing to his own ’33 model. Dilley mentioned that he was going to send his to Canada to have its engine traded in for an electric one.

“And I swear the guy’s face… there’s a top to bottom transformation,” Dilley laughs. “You know, from joy and excitement about the car to like, ‘What the fuck is wrong with you?’”

Dilley himself had a moment of uncertainty when Webb found the ’69 Camaro to convert. The model Webb got his hands on had only 69 miles on its odometer, and the numbers on the hood, the wheels and the chassis all matched. A rare mint condition car.

Webb says its owner almost didn’t sell it to him. Dilley almost didn’t let it get converted.

It took Dilley a week to make up his mind. “I was wondering if it was the right thing to do,” he says. “And eventually I realized it was.”

There are several ways to look at the “right thing” that Dilley is talking about. In the carbon equation of climate change, classic cars are but a miniscule fraction of the number of combustion engine cars on the road today. For Maliteare, though, the payoff is experiential.

“It makes the vehicle more enjoyable,” he says. “Instead of ‘the battery’s dead, the carburetor is faulty, the gas is stale, the car won’t start,’” Maliteare shrugs. “Electric is more usable for life in 2021.”

Then there’s Emily Webb assessment. “We’re giving the car longevity,” she says, “And we’re reusing something that is already manufactured instead of creating something new.”

Her dad Chris greatly admires the efficiency of electric motors. Most combustion engines need to rev up to thousands of revolutions per minute to deliver maximum torque, which in turn affects acceleration. But an electric motor generates the same amount of torque at one RPM that the Bel Air would get at 5,000 RPM on its original engine.

That efficiency makes electric cars quicker — some jumping from zero to 100 kilometres per hour in 2.5 seconds — than cars with combustion engines. A Tesla can accelerate faster than a Ferrari or a Porsche, even if those cars would eventually hit their top speeds and outstrip the Tesla.

John Stonier, who does the accounting at canEV and is president of the Vancouver Electric Vehicle Association, attests to such performance. One overcast day in Vancouver, a 600-horsepower Maserati pulled up next to him on Pacific Avenue by BC Place stadium. Stonier didn’t want to make a fuss, but the Maserati’s obnoxious revving irked him.

“He was asking for it,” Stonier says adamantly. “He had an open-neck shirt, a gold chain, a cigarette… he wanted the attention.”

Stonier decided to “piss him off a little.” The light changed and Stonier stepped on the accelerator. He heard a whine from the Maserati as the engine revved, then a growl as it caught, and then it really began to power up when it hit 5,000 RPM.

By then Stonier was two blocks ahead — in his base-model, four-door family sedan, the Nissan Leaf.

“It was like night and day,” Stonier laughs.

At the end of the two blocks, just as the Maserati began to catch up, Stonier turned off the road. His wife looked over from the passenger seat to tell him, “You’re acting like a 16-year-old.”

He had to agree. Then he smiled to notice the car wasn’t even at full power. “I was in eco mode,” he says.

Photo by Pallavi Rao.

Dilley says that if he were to convince a vintage car owner to go electric, he’d find out what they care about. “Power, reliability, economy or environment?” he rattles off.

There’s something for everyone. Even the man who’d balked at the conversion of the ’32 Ford eventually came around enough to hear Dilley out. And when Webb responded politely to the man who questioned his masculinity, somehow he gained a fan.

It comes down to a personal place where passion meets practicality. An owner of an electric-converted classic will probably drive their car more because it needs less maintenance. They’ll spend less money on its upkeep. And the retro-beauty of the car’s lines remain for all to admire and wave at as you drive by.

For Dilley it’s about the visceral experience of not just possessing but using his three vintage hot rods. Because they are electric, he says, driving them will “be more fun, you know?”

He pauses, seeming to imagine roads ahead.

“It’ll be more fun!” ![]()

More Stories

Old Mustangs for Sale: Navigating the Allure of a Classic Ride

Vintage Mercedes: Unveiling Timeless Elegance and Engineering Mastery

Hemmings Classic Cars: Timeless Beauty on Four Wheels